Reg's Boundary Bend

|

By Reg Dean, Robinvale (From his tape recordings made up to June 1988)

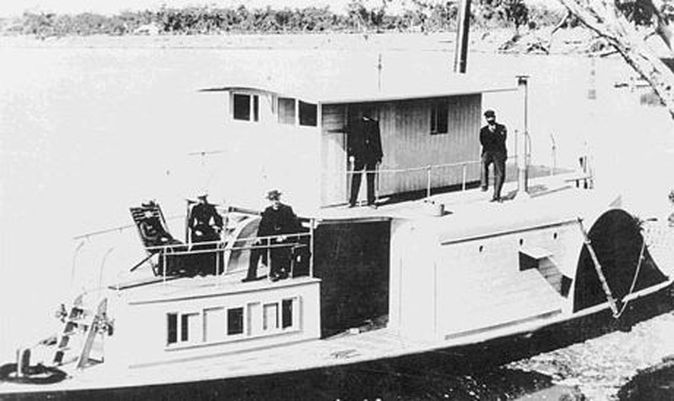

Italics: means added or amended text from the original source. In 1917 the Dean family, with dad John Francis and wife Evelyn Emily, children Francis, Reginald and Doris travelled on the paddle steamer “Ruby” from Mildura to Boundary Bend at a cost of 2 pounds 10 shillings. They later added William, Hazel and Evelyn to the family. |

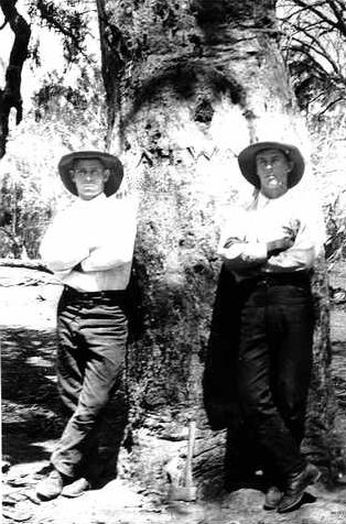

Reg in 1929

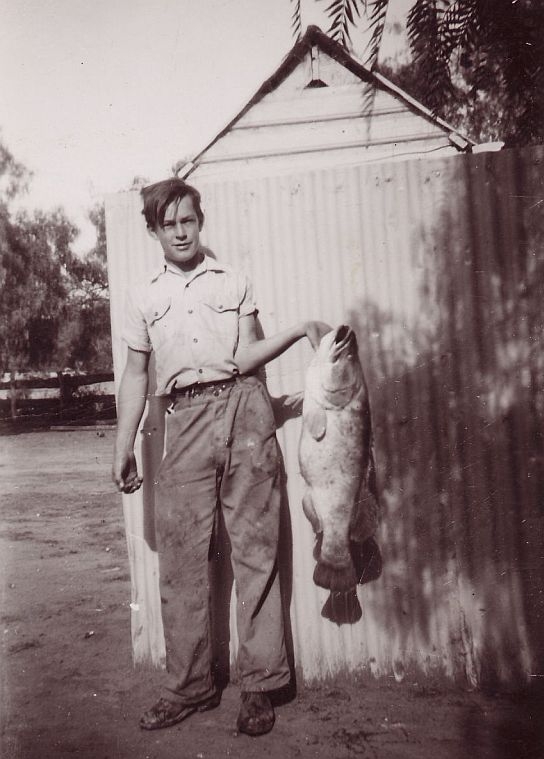

Reg in 1942

|

|

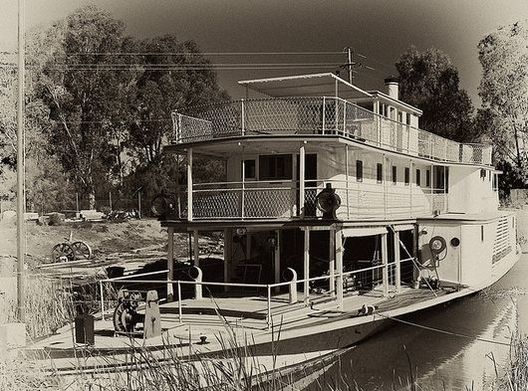

The Paddle Steamer ‘Ruby’ (pictured), that the Deans’ family sailed up the Murray to Boundary Bend from Mildura in November, 1917. PS Ruby was built at Morgan in SA by David Milne in 1907 for Captain Hugh King. Ruby ceased its usual return route from Morgan to Swan Hill in the 1930’s. It was re-commissioned in 2004.

Boundary Bend Early Years

Mrs Alec Conner had employed Mr Jack Dean to work on her citrus and vines farm. The manager was Mr Robert O’Bree. Boundary Bend was then half jokingly called "Robert O’Bree’s Town" (See the O’Bree Family story later). He had provided the school. The building was of drop-log construction with a roof of secondhand corrugated iron. It had been built behind the wine shanty, known as the Wine Shades. In 1918 Miss Mary Cross was the teacher.

|

When it rained heavily, the roof leaked. Miss Cross asked the biggest boy, Eddie Pearce (an Aboriginal lad) to count the holes in the roof and the result was then published in the Swan Hill newspaper, the Guardian. Mr O’Bree was furious. He declared that Miss Cross was not a suitable person to be teaching their children and her employment was terminated. In about 1922, Mr O’Bree built a new school of pine weatherboard construction. It was opened on 1 March,1922. Everyone was very impressed with this. It was referred to as the Pine School and given the number 4089. A later teacher was Miss Dudley, a big strong woman, who was rather free with the cane. She unjustly accused Reg of stealing money from her and caned him to bleeding for it, but his father believed Reg’s story and stood up for him. She caned Eddie Pearce another time, catching his fingernail and there was blood s everywhere.

|

This is how the old Pine School site looks today. Only the water tank stand upright posts still remain. The photograph has been taken practically from the same spot, nearly 90 years ago, from when the original was taken.

The Deans' old log home was located behind the peppercorn trees in the background. |

|

In late 1925 the Education Department built a new school and transferred the number 4089 to it. Jack Dean said it was too damn flash for Boundary Bend.

(pictured left, the Boundary Bend State School No. 4089 in ca.1926. Reg and Frank Dean and Eddie Pearce can be seen standing together at the centre back) |

Boundary Bend Stories

|

John Francis Dean

|

Our dad Jack Dean was a handy man. He used to do some soldering and he kept the flux (spirits of salts) in a lemon essence bottle on a high shelf. Evelyn, his wife, ran out of lemon essence, saw the bottle up there and put some of the stuff in a cake she was making. Robert Dunne (a family friend) happened to be visiting and he recognized the smell before anyone ate any. Just as well.

|

Evelyn Emily Dean

|

A retired nurse lived on one of the boats and she looked after the cuts and bites and accidents. The nearest doctor was in Mildura or Swan Hill, where the women went to have their babies. Mrs Higgins, Lionel’s mother was very good as a nurse too.

In 1924 there was a bad mouse plague. The school teacher couldn’t handle it and she left. The mice ran everywhere, made holes in the walls of the bag shacks where some people lived and bit the ears and toes of small children while they slept. All the food had to be hung from the roof in bags with a tin plate on the rope so the mice couldn’t get at it. If you had a wire food safe the legs were stood in jam tins full of water with a bit of kerosene to keep the mice away. Everything smelled of mice. You could put an empty flour bag on the ground with the opening propped with a brick. Mice would crowd into it overnight chasing the smell of the flour. In the morning a man would swing the bag against a tree to kill the mice killing maybe 50 of them, but it didn’t make any difference to the numbers. Cats were sick of mice, they wouldn’t touch them. The magpies that some people had as pets would play with them and kill them but not eat them. The plague ended and the mice disappeared as quick as they came.

When people were living in bag shacks they didn’t have a proper stove to cook in. They would use a camp oven set on bricks over an open fire in a shallow hole front of the hut. Often bread was not available and the women made scone loaf. It was flour with cream of tartar and soda. Nowadays, you would have self raising flour but it wasn’t invented then. It was mixed with water and a bit of salt, made into a long roll then formed into a ring round the inside of the camp oven. Flour was bought in a 50 pound bag. Most people had old Army blankets, grey with a blue stripe down the middle. They were bought from Disposals in Mildura or Swan Hill and were good value for money.

"Cocky chaff” was the husks of wheat that were blown away when they were winnowing. There’s not much nourishment in it, but they’d feed it to the horses when they were starving and there was nothing else to be had. There was no running water. It had to be carted by hand from the river. Mr Dean built a little jetty into the lagoon behind Conners so they could get water from the clear part away from the edge. No-one had a garden. Water was too precious to waste on that.

The Dean boys would sometimes tease Mrs O’Bree. They’d tie a piece of cotton on her door handle, hide behind a bush a little way away and give the cotton a pull. Mrs O’Bree would come to the door to see who was there, no-one of course. After a while they would do it again and waste Mrs O’Bree’s time. One of the O’Bree boys, Ron known as "Skillix", threatened to kick the Deans for tormenting their mother. Frank threw a half brick at him and stunned him. The Deans ran away as he fell on the sandy road. They thought they had killed him.

The O’Brees had a pigsty loosely roofed with sheets of iron. The Deans pinched 2 sheets to bend into little boats for going out on the lagoon. The pigsty was 50 yards or more from the O’Brees house. Mrs O’Bree was an expert with a big stockwhip and when the Dean and O’Bree boys were arguing about, she swung and cracked the whip at them all. The Deans kept out of her way for a while after that.

There was an old shed on Woodhead’s place and it still had some of the things left from when they used to render down old sheep and dead ones to get the fat for making candles. Sometimes people would come and get the meat from it too. In one comer there were some rotting bags with what looked like cement spilling out. Tom Lawrence said "Don’t you boys touch it, it’s grey arsenic!"

There is a hump of rocks in the river near Boundary Bend that only showed when the water was low. They called it Jeremiah’s Lump. Some of the older kids, Pearces, O’Brees, Deans, Conners and others, used to swim at a sandbar near there. I it wasn’t too safe and there were a few near-drownings. The kids looked out for each other though Ted O’Bree saved a few kids there. He was a bit older and a very good swimmer.

By 1926 or so when Robert O’Bree was getting on a bit he liked to talk to Mrs Dean. He wanted to know everything that was going on round the place. He was keen to see the town grow a bit. People would come along the road from Swan Hill to Mildura and look around the place. It wasn’t a sealed road, just formed sand.

At a place up the Murrumbidgee towards Balranald they had barges wired end to end across the river to form a bridge with a railing along one side. Each barge was about 16 feet long, 5 feet wide and 18 inches deep. They’d drive sheep across it when they needed to get to the other side. In a flood, the wires broke and one of the barges floated right downstream to Boundary Bend. The barges were made of good Kauri timber, but this one got pretty battered on the way. Jack Dean grabbed it and repaired it. He was a handy carpenter and he made a little shed on it too. The boys slept in it at times.

In 1924 there was a bad mouse plague. The school teacher couldn’t handle it and she left. The mice ran everywhere, made holes in the walls of the bag shacks where some people lived and bit the ears and toes of small children while they slept. All the food had to be hung from the roof in bags with a tin plate on the rope so the mice couldn’t get at it. If you had a wire food safe the legs were stood in jam tins full of water with a bit of kerosene to keep the mice away. Everything smelled of mice. You could put an empty flour bag on the ground with the opening propped with a brick. Mice would crowd into it overnight chasing the smell of the flour. In the morning a man would swing the bag against a tree to kill the mice killing maybe 50 of them, but it didn’t make any difference to the numbers. Cats were sick of mice, they wouldn’t touch them. The magpies that some people had as pets would play with them and kill them but not eat them. The plague ended and the mice disappeared as quick as they came.

When people were living in bag shacks they didn’t have a proper stove to cook in. They would use a camp oven set on bricks over an open fire in a shallow hole front of the hut. Often bread was not available and the women made scone loaf. It was flour with cream of tartar and soda. Nowadays, you would have self raising flour but it wasn’t invented then. It was mixed with water and a bit of salt, made into a long roll then formed into a ring round the inside of the camp oven. Flour was bought in a 50 pound bag. Most people had old Army blankets, grey with a blue stripe down the middle. They were bought from Disposals in Mildura or Swan Hill and were good value for money.

"Cocky chaff” was the husks of wheat that were blown away when they were winnowing. There’s not much nourishment in it, but they’d feed it to the horses when they were starving and there was nothing else to be had. There was no running water. It had to be carted by hand from the river. Mr Dean built a little jetty into the lagoon behind Conners so they could get water from the clear part away from the edge. No-one had a garden. Water was too precious to waste on that.

The Dean boys would sometimes tease Mrs O’Bree. They’d tie a piece of cotton on her door handle, hide behind a bush a little way away and give the cotton a pull. Mrs O’Bree would come to the door to see who was there, no-one of course. After a while they would do it again and waste Mrs O’Bree’s time. One of the O’Bree boys, Ron known as "Skillix", threatened to kick the Deans for tormenting their mother. Frank threw a half brick at him and stunned him. The Deans ran away as he fell on the sandy road. They thought they had killed him.

The O’Brees had a pigsty loosely roofed with sheets of iron. The Deans pinched 2 sheets to bend into little boats for going out on the lagoon. The pigsty was 50 yards or more from the O’Brees house. Mrs O’Bree was an expert with a big stockwhip and when the Dean and O’Bree boys were arguing about, she swung and cracked the whip at them all. The Deans kept out of her way for a while after that.

There was an old shed on Woodhead’s place and it still had some of the things left from when they used to render down old sheep and dead ones to get the fat for making candles. Sometimes people would come and get the meat from it too. In one comer there were some rotting bags with what looked like cement spilling out. Tom Lawrence said "Don’t you boys touch it, it’s grey arsenic!"

There is a hump of rocks in the river near Boundary Bend that only showed when the water was low. They called it Jeremiah’s Lump. Some of the older kids, Pearces, O’Brees, Deans, Conners and others, used to swim at a sandbar near there. I it wasn’t too safe and there were a few near-drownings. The kids looked out for each other though Ted O’Bree saved a few kids there. He was a bit older and a very good swimmer.

By 1926 or so when Robert O’Bree was getting on a bit he liked to talk to Mrs Dean. He wanted to know everything that was going on round the place. He was keen to see the town grow a bit. People would come along the road from Swan Hill to Mildura and look around the place. It wasn’t a sealed road, just formed sand.

At a place up the Murrumbidgee towards Balranald they had barges wired end to end across the river to form a bridge with a railing along one side. Each barge was about 16 feet long, 5 feet wide and 18 inches deep. They’d drive sheep across it when they needed to get to the other side. In a flood, the wires broke and one of the barges floated right downstream to Boundary Bend. The barges were made of good Kauri timber, but this one got pretty battered on the way. Jack Dean grabbed it and repaired it. He was a handy carpenter and he made a little shed on it too. The boys slept in it at times.

|

There were many ways to earn a bit of money. The Royal Melbourne Hospital let it be known that they wanted striped leeches. There was a little banana shaped lagoon they called Leech Lagoon behind the bigger one near the Conners. If you just made a noise walking past the bank, you could see the leeches come swimming toward you.

|

|

The Dean boys would stand in the water for 10 seconds, run to the bank and pull 3 or 4 leeches off their legs. Then they had a better idea. They’d kill a rabbit, rub some blood on a board and lay that in the water. After a bit they’d turn it over and there’d be a dozen or more leeches. Jack Dean would collect them into a big green treacle tin with holes punched in it. With a bit of wet grass, 100 leeches would fit in a 7 pound tin and off it would go to the Melbourne hospital on the train from Yungera. The hospital paid ten shillings a hundred for them until they didn’t need them anymore.

|

|

The Deans used to get young cockies from the nest and keep them for awhile, teach them to “kiss cocky”, dance and talk a bit. Then they’d sell them. A pound for a white cocky and ten shillings for a rock pebbler. A woman had heard about the birds and she came all the way from Melbourne to get one. She was really happy to get it and planned to show her friends.

There weren’t nearly as many cockies about as there are now and the only Corellas were up the Darling. To get the young birds Jack Dean made a ladder of 4 strands of l2 gauge wire with a mallee stick twisted in every 12 inches or so. It could be rolled up and you’d put a long stick through the middle of the roll and two men carry it with one each end. You’d put it in the boat and row to where there was a likely tree. With long sticks the ladder would be pushed up the tree and the end hooked over a broken branch. Then a lad, often Reg, would climb up to get the birds out of the nest and they’d be taken home to start training them to talk.

|

Rock Pebbler

|

There were thousands of frogs in the lagoons and along the river. They were collected as bait for the fishermen’s’ crosslines. Green frogs, tree frogs, marbled frogs. They were under bark, swimming in the lagoons, in the dry leaves on the bank. They had never heard of using bardi grubs as bait for cod.

There were plenty of snakes. In warm weather it was nothing to see l0 of them in a day. Tiger snakes didn’t grow very long, but they could get quite fat. There were black and brown snakes and you’d be careful of them all.

There were great flocks of ducks, every kind you could think of, nesting in the hollow trees. Getting the eggs from the wild ducks was one of the ways that people on the bread line survived, they were good food and you could cook them in different ways. Black duck, teal, wood duck, musk duck, blue duck, white eyes (also called hardhead and barking duck), widgeon, bar-wings, even the beautiful mountain duck at times. In those days they had a duck season opening the first or second week in February. There were duck swamps near Boundary Bend on the Canally (N.S.W.) side of the river. Boatloads of shooters would come from other places, 15 or 20 men. There were clouds of ducks and no bag limits, they would load up the 2 or 3 boats and be gone by 11 a.m. Boys would go out in the knee deep water then and get the wounded ducks that they left behind, maybe a dozen of them. Empty shot gun shells were everywhere, all colours, blue, red, green, purple and the famous black shells. The soft duck feathers were sometimes used to stuff pillows for the beds.

There were plenty of snakes. In warm weather it was nothing to see l0 of them in a day. Tiger snakes didn’t grow very long, but they could get quite fat. There were black and brown snakes and you’d be careful of them all.

There were great flocks of ducks, every kind you could think of, nesting in the hollow trees. Getting the eggs from the wild ducks was one of the ways that people on the bread line survived, they were good food and you could cook them in different ways. Black duck, teal, wood duck, musk duck, blue duck, white eyes (also called hardhead and barking duck), widgeon, bar-wings, even the beautiful mountain duck at times. In those days they had a duck season opening the first or second week in February. There were duck swamps near Boundary Bend on the Canally (N.S.W.) side of the river. Boatloads of shooters would come from other places, 15 or 20 men. There were clouds of ducks and no bag limits, they would load up the 2 or 3 boats and be gone by 11 a.m. Boys would go out in the knee deep water then and get the wounded ducks that they left behind, maybe a dozen of them. Empty shot gun shells were everywhere, all colours, blue, red, green, purple and the famous black shells. The soft duck feathers were sometimes used to stuff pillows for the beds.

Jack Dean had made an 18-foot boat he called the “Doris” after his eldest daughter. Mum, all the kids, the little dog Turk and even an occasional visitor could all go in it together. It was a good boat and well made. Mrs Dean didn’t row. She had only one good arm having been crippled by polio when she was a child. If there was a likely nest in a tree Jack would bump the boat against the trunk. A hollow in the tree with duck down around the opening showed that ducks were nesting there. A duck in there sitting on eggs would fly out when the tree was knocked. Then one of the boys would climb up, take out an egg and pass it down to Jack. He would tap it gently to listen if it was any good. They would take all but 2 or 3 eggs and go home at night with as much as a kerosene tin full. That was the family’s feed for a week. Once in flood time the family went up Summer’s Creek, upstream from Boundary Bend, looking to get some duck eggs. The water was fairly rushing in the creek as well as the main river, the current was very strong. Bob Dunne, a family friend, was with them and Jack left Bob and the kids while he went with Mrs Dean to check out the trees. It would be easier to manage the boat in the fast flood with only one passenger in it. Jack said to his wife, "Quick, bob down there’s a low branch." She wasn’t quick enough and grabbed at the branch with her good hand as the boat speared on, leaving her hanging there with her body in the rushing water. Jack was good on the oars but had no hope of backing up in the fast water. He had to go back up along the bank and come down in mid stream to come under his wife again.

Bob was holding the baby (Evie). He wanted to drop her and swim out to help Mrs Dean and in the panic the dog started barking at a tiger snake. Bob tried to grab a stick to hit at the snake and Frank was trying to grab the baby. The younger kids were howling. Jack was yelling to his wife "Hold on there!" and she was hanging on for her life. Jack came back down in the current and grabbed Mrs Dean, Frank got the baby, the boat hit the tree hard but didn’t break and everyone was crying with relief when they got onto the bank together. They went on after a while and got a fair lot of eggs but they didn’t remember the day as a good time.

One day Reg caught a hare and they cooked it on the little Daisy stove with carrots and peas that Jack had brought home from work at Conners. The family was going out egg hunting again. They put the nearly-cooked meal into a camp oven sitting on bricks over a slow burning fire so it would be all ready to eat when they got home. They had a whippet called Pippi that stayed home. When they got home the oven was lying on its side empty and the whippet was full. It had tipped the oven over and eaten the lot.

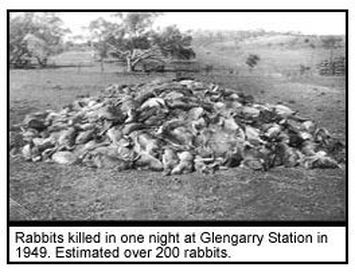

Everyone those days ate a lot of rabbits and fish. There was a plague of rabbits. They were all over the place. Canally Station was on the NSW side, just above where the 'Bidge joined the Murray and there were hordes of rabbits there. Tom Pearce senior and Robert Dunne were employed to lay baits and poison them. They had to use a dreadful poison known as SAP. This was a mixture of strychnine, arsenic and phosphorus. They had to mix it themselves and it was generally used by lacing pollard with it. Tom Pearce (TeePee), our aboriginal, friend, was employed by Canally Station to poison rabbits. He had to use SAP. He had a horse pulling a sort of cart with a seat across it and a disc under it to cut a line where he laid the baits. When there was no pollard, Tee Pee used chopped up thistle roots. SAP looked like treacle and had a liquorice smell. The Dean family often got water from the lagoon behind Conners’ place. It saved the long drag from the river with heavy buckets. They got clear water from Jack’s little jetty where it wasn’t muddy at the edge. One time the whole family got sick with diarrhoea and vomiting. Poking round in the lagoon one day Frank found a rusty old tin with no label and an oily scum on the water round it. Frank recognized the smell of SAP and told his father, who found a second tin, near where they had been getting water. They had been discarded there and forgotten. No more water was taken from there for a while.

Another way to attack the rabbits was to yard and shoot them. There was a good market for the skins. McMillan, Bordevitch and Dunstan came and they employed Lionel Higgins and Reg Dean as a couple of youngsters to help them. The boys had to be able to handle a gun. Lionel had a single shot rifle and Reg got a little Scout pea rifle. It cost twenty two shillings and sixpence, bought by mail from an advertisement in the Leader newspaper. Bunnies were so thick that if you clapped your hands the whole countryside moved. McMillan and Co would pick an area where the rabbits were particularly thick to yard them. They carried rolls of netting 18 inches wide in a spring cart. Support pegs were cut from the bush. Wire was laid out in a V shape, half a mile long, with wider wire to go at the point of the V, where the rabbits would be driven. The open end was 20 or 30 feet across. The pegs were set upright in the ground and the netting was tied to them with wires. This was all done as quietly and with as little fuss as possible and then they’d stay away to give the place a spell for a few days and to give the rabbits time to get used to the wire.

One day Reg caught a hare and they cooked it on the little Daisy stove with carrots and peas that Jack had brought home from work at Conners. The family was going out egg hunting again. They put the nearly-cooked meal into a camp oven sitting on bricks over a slow burning fire so it would be all ready to eat when they got home. They had a whippet called Pippi that stayed home. When they got home the oven was lying on its side empty and the whippet was full. It had tipped the oven over and eaten the lot.

Everyone those days ate a lot of rabbits and fish. There was a plague of rabbits. They were all over the place. Canally Station was on the NSW side, just above where the 'Bidge joined the Murray and there were hordes of rabbits there. Tom Pearce senior and Robert Dunne were employed to lay baits and poison them. They had to use a dreadful poison known as SAP. This was a mixture of strychnine, arsenic and phosphorus. They had to mix it themselves and it was generally used by lacing pollard with it. Tom Pearce (TeePee), our aboriginal, friend, was employed by Canally Station to poison rabbits. He had to use SAP. He had a horse pulling a sort of cart with a seat across it and a disc under it to cut a line where he laid the baits. When there was no pollard, Tee Pee used chopped up thistle roots. SAP looked like treacle and had a liquorice smell. The Dean family often got water from the lagoon behind Conners’ place. It saved the long drag from the river with heavy buckets. They got clear water from Jack’s little jetty where it wasn’t muddy at the edge. One time the whole family got sick with diarrhoea and vomiting. Poking round in the lagoon one day Frank found a rusty old tin with no label and an oily scum on the water round it. Frank recognized the smell of SAP and told his father, who found a second tin, near where they had been getting water. They had been discarded there and forgotten. No more water was taken from there for a while.

Another way to attack the rabbits was to yard and shoot them. There was a good market for the skins. McMillan, Bordevitch and Dunstan came and they employed Lionel Higgins and Reg Dean as a couple of youngsters to help them. The boys had to be able to handle a gun. Lionel had a single shot rifle and Reg got a little Scout pea rifle. It cost twenty two shillings and sixpence, bought by mail from an advertisement in the Leader newspaper. Bunnies were so thick that if you clapped your hands the whole countryside moved. McMillan and Co would pick an area where the rabbits were particularly thick to yard them. They carried rolls of netting 18 inches wide in a spring cart. Support pegs were cut from the bush. Wire was laid out in a V shape, half a mile long, with wider wire to go at the point of the V, where the rabbits would be driven. The open end was 20 or 30 feet across. The pegs were set upright in the ground and the netting was tied to them with wires. This was all done as quietly and with as little fuss as possible and then they’d stay away to give the place a spell for a few days and to give the rabbits time to get used to the wire.

|

They would then move in a line towards the opening of the netting, driving the rabbits in front of them, clapping or hitting a tree now and then to make a little noise and keep them moving. lf a rabbit squatted and didn’t move on they could shoot him through the eye or neck, they were only after undamaged skins, nothing else. The men were moving closer to each other as they came to the net and the rabbits were thick, running on top of each other as they were driven forward.

|

|

Then McMillan would pull the wire across the open end as a gate and the men got in among the rabbits. You’d grab one rabbit after another, break its neck and throw it onto the pile in the middle of the yard. In one of the yardings they got over two thousand and they had 4 yardings before the numbers thinned out. Then would come the big job of skinning them all. Sometimes the men would go out leaving one man at the camp to cook for the rest of them. Often you’d have rabbit stew but everyone got very tired of that.

|

There was hare, parrot or duck, cooked in a camp oven over an open fire. Once one of the boys cooked parrots without gutting them first, that didn’t go down too well. The Deans and Pearce boys would take their dogs and go rabbiting over the river and build up a pile of skins on the bank there. Then Jack Dean would cart them back across the river to Boundary Bend to send them away for sale.

Jack Dean built a bag shack on the river 100 yards off the river on Rowes’ place near Buchanans’ and they were fishing there and Frank, Reg and Bill with him. They had the punt with a shed on it to sleep in. He built another shack near the Meridian Road for Mrs Dean and the girls and they stayed there. Jack became ill and died in Swan Hill. He was buried in the cemetery at Bannerton. The boys moved down to Robinvale and they never did go back to Boundary Bend.

The Pearce Family in Boundary Bend

(An Aboriginal family from Boundary Bend and later Balranald)

Reg Dean has these memories of the Pearces’ with whom he and his brothers shared life in Boundary Bend for a few years from about 1919. The father was Tom, known as TeePee. There was a son Tom too. There were 9 Pearce children altogether and 4 or 5 of them went to school with Reg. At first they lived in a camp downstream a bit from the main part of the little settlement. It was in the box gum timber near where the old Boundary Bend football ground was. There is to this day, wire around some of the trees and a few bricks from their fireplace. There was Myrtle, Clarrie, Eddy and Tommy, being the children that Reg mentioned.

The Deans did a lot with the Pearce kids, chased rabbits (and there were plenty of them) with their dogs and swam from sandbanks in the river. The Pearces showed the Deans how to tie their shirts and shorts in a bundle and put it on their heads with a belt under their chin to hold it, while they swam across the river. Sometimes the clothes would get wet but mostly not. They would catch rabbits, skin them, dry and bale the skins and when they had a pile of them Mr Dean would bring them back over the river in his fishing boat the “Doris”. They had 3 or 4 dogs, mongrel mixtures. The Dean boys (Frank and Reg) only had one dog but they were all pretty fast.

Tommy and Reg would play wrestle at school to amuse the other kids. They were the same age and the same size so it was a fair match. There was a man who hated to see kids fighting and he didn’t know when it was serious. One day he tried to stop Tommy and Reg. Reg turned away to see what he was on about and Tommy landed him with the best black eye he ever had.

Reg and Tommy had birthdays in the same month and Tommy would share a birthday with Reg. Once Mrs Dean put hundreds and thousands on a cake and they were the first ones Tommy had ever seen. He was bug-eyed with amazement.

The older brother, Eddy was the big boy at school and the teacher would ask him to do jobs for her. Robert O’Bree had built the school. He used second hand corrugated iron for the roof and when it rained the roof leaked through the holes. The teacher was Miss Mary Cross and she once asked Eddy to count the leaking holes. She reported the results to the Swan Hill paper and Mr O’Bree was very annoyed. Arthur Kirby was there too. He was brother to TeePee’s wife, Lalla. He shared the work on the Dean fishing nets at one time.

Jack Dean built a bag shack on the river 100 yards off the river on Rowes’ place near Buchanans’ and they were fishing there and Frank, Reg and Bill with him. They had the punt with a shed on it to sleep in. He built another shack near the Meridian Road for Mrs Dean and the girls and they stayed there. Jack became ill and died in Swan Hill. He was buried in the cemetery at Bannerton. The boys moved down to Robinvale and they never did go back to Boundary Bend.

The Pearce Family in Boundary Bend

(An Aboriginal family from Boundary Bend and later Balranald)

Reg Dean has these memories of the Pearces’ with whom he and his brothers shared life in Boundary Bend for a few years from about 1919. The father was Tom, known as TeePee. There was a son Tom too. There were 9 Pearce children altogether and 4 or 5 of them went to school with Reg. At first they lived in a camp downstream a bit from the main part of the little settlement. It was in the box gum timber near where the old Boundary Bend football ground was. There is to this day, wire around some of the trees and a few bricks from their fireplace. There was Myrtle, Clarrie, Eddy and Tommy, being the children that Reg mentioned.

The Deans did a lot with the Pearce kids, chased rabbits (and there were plenty of them) with their dogs and swam from sandbanks in the river. The Pearces showed the Deans how to tie their shirts and shorts in a bundle and put it on their heads with a belt under their chin to hold it, while they swam across the river. Sometimes the clothes would get wet but mostly not. They would catch rabbits, skin them, dry and bale the skins and when they had a pile of them Mr Dean would bring them back over the river in his fishing boat the “Doris”. They had 3 or 4 dogs, mongrel mixtures. The Dean boys (Frank and Reg) only had one dog but they were all pretty fast.

Tommy and Reg would play wrestle at school to amuse the other kids. They were the same age and the same size so it was a fair match. There was a man who hated to see kids fighting and he didn’t know when it was serious. One day he tried to stop Tommy and Reg. Reg turned away to see what he was on about and Tommy landed him with the best black eye he ever had.

Reg and Tommy had birthdays in the same month and Tommy would share a birthday with Reg. Once Mrs Dean put hundreds and thousands on a cake and they were the first ones Tommy had ever seen. He was bug-eyed with amazement.

The older brother, Eddy was the big boy at school and the teacher would ask him to do jobs for her. Robert O’Bree had built the school. He used second hand corrugated iron for the roof and when it rained the roof leaked through the holes. The teacher was Miss Mary Cross and she once asked Eddy to count the leaking holes. She reported the results to the Swan Hill paper and Mr O’Bree was very annoyed. Arthur Kirby was there too. He was brother to TeePee’s wife, Lalla. He shared the work on the Dean fishing nets at one time.

Old TeePee could strip a canoe and the only one Reg ever saw done properly. TeePee stripped the bark from a gum tree to make quite a big canoe, 7 or 8 feet long. He dug a hole in the sand by the river the size and shape of the canoe and let the bark down into the hole by ropes. It was pretty heavy. This time in letting it down, he split one end of the bark for about a foot and he was most upset. He said it was no good any more. But anyway he cured it, filled it with dead leaves as it was down in the hole and set fire to them. The Deans thought he was mad. He was burning it after all that work. It was in the hole with the green side of the bark up and it didn’t burn, it only heated it up enough to dry it out a bit and toughen it. Then he filled the bark with sand, shaping it with the dirt as he filled it. It had to stay there and cure for a while. TeePee said "I won’t ever use it, I couldn’t take my family in it. It wouldn’t be safe. I give it to you Dean boys to paddle round the lagoon in." After a while the Deans got the canoe out and they took it to the lagoon early one morning before school.

It was winter and they had coats and boots on. They had wired up the little split in one end of the canoe. They took it out into the deeper water and when they moved round in it there was a rip and the canoe slowly fell in half. Frank dived for the bank. Reg got onto a log lying out into the water. The log was alive with big green ants and they bit Reg all over, so he looked as though he had chicken pox. Tommy knew better though. He knew what ant bites looked like.

In those days if the boys didn’t behave they were hit with a cane. Once the teacher hit Eddie, caught his fingernail and nearly pulled it off and there was blood everywhere. There was no piped water or anything fancy like that. They had to get the water in buckets from the river and carry it up the bank. Myrtle used to get it for the Pearces. Frank and Reg got it for the Deans. You didn’t have a garden and every bit of water was used carefully. Deans kept the feathers from the ducks they ate to stuff pillows, but the Pearces had pillows stuffed with emu feathers. The feathers were long and springy and good to sleep on.

TeePee had a khaki military coat and sometimes Tommy would wear it to school. When Reg was starving hungry he would sometimes go to the Pearce camp and they would give him a feed. A piece of emu or spoonbill cooked in a camp oven or a firepit was a good meal. Old TeePee was a good shot with a Frankel rifle that he had and he would shoot a spoonbill for a feed. As an aboriginal, he was allowed to but they were protected birds for us. Eddie would also go hunting with him and carry things home. He would carry an emu, gutted, with the stomach against the back of his neck and the legs crossed across the front of him.

In about 1926 Jack Dean went into town to pick up some supplies. His transport had now progressed to a horse and buggy. For company, he took with him his 5 year old daughter, Hazel. While he was in the store getting the supplies, the horse lifted its tail and commenced to do its business. Hazel was very intrigued, so she reached over and with the end of the whip handle, shoved it into that nasty wrinkled gap. Of course the horse bolted off down the road, with Hazel holding on for dear life. Jack came out and took off after them. Two miles down the road he found the pair. The horse was having a drink and Hazel was still holding onto the buggy seat trembling and crying. Jack said later to Reg and Frank that she stuffed that one up.

About 1927 or 28 when the boys were into their teens, the Dean boys would go goanna hunting with Clarrie and Tommy Pearce. Eddie didn’t join in then. There were black goannas, grey ones and little spotted ones. The dogs would rout them out and the goanna would race up the nearest tree, leaving the dogs barking at the bottom. The boys had a long thin pointed pole, like a wireless aerial and they would push it up through the tree 30 feet or more, to prod the goanna and make him fall. Sometimes a dog would get him before he got to the next tree, but the boys didn’t kill them and they usually got away.

Around Christmas, the Pearces would pack up everything and they would all swim across the Murray River and walk to Balranald about 15 miles away. They would camp a night or two on the way. When they were in Balranald around Christmas 1928, the shack where they lived in Boundary Bend burned down and after that they stayed in Balranald. They never came back to live in Boundary Bend.

In those days if the boys didn’t behave they were hit with a cane. Once the teacher hit Eddie, caught his fingernail and nearly pulled it off and there was blood everywhere. There was no piped water or anything fancy like that. They had to get the water in buckets from the river and carry it up the bank. Myrtle used to get it for the Pearces. Frank and Reg got it for the Deans. You didn’t have a garden and every bit of water was used carefully. Deans kept the feathers from the ducks they ate to stuff pillows, but the Pearces had pillows stuffed with emu feathers. The feathers were long and springy and good to sleep on.

TeePee had a khaki military coat and sometimes Tommy would wear it to school. When Reg was starving hungry he would sometimes go to the Pearce camp and they would give him a feed. A piece of emu or spoonbill cooked in a camp oven or a firepit was a good meal. Old TeePee was a good shot with a Frankel rifle that he had and he would shoot a spoonbill for a feed. As an aboriginal, he was allowed to but they were protected birds for us. Eddie would also go hunting with him and carry things home. He would carry an emu, gutted, with the stomach against the back of his neck and the legs crossed across the front of him.

In about 1926 Jack Dean went into town to pick up some supplies. His transport had now progressed to a horse and buggy. For company, he took with him his 5 year old daughter, Hazel. While he was in the store getting the supplies, the horse lifted its tail and commenced to do its business. Hazel was very intrigued, so she reached over and with the end of the whip handle, shoved it into that nasty wrinkled gap. Of course the horse bolted off down the road, with Hazel holding on for dear life. Jack came out and took off after them. Two miles down the road he found the pair. The horse was having a drink and Hazel was still holding onto the buggy seat trembling and crying. Jack said later to Reg and Frank that she stuffed that one up.

About 1927 or 28 when the boys were into their teens, the Dean boys would go goanna hunting with Clarrie and Tommy Pearce. Eddie didn’t join in then. There were black goannas, grey ones and little spotted ones. The dogs would rout them out and the goanna would race up the nearest tree, leaving the dogs barking at the bottom. The boys had a long thin pointed pole, like a wireless aerial and they would push it up through the tree 30 feet or more, to prod the goanna and make him fall. Sometimes a dog would get him before he got to the next tree, but the boys didn’t kill them and they usually got away.

Around Christmas, the Pearces would pack up everything and they would all swim across the Murray River and walk to Balranald about 15 miles away. They would camp a night or two on the way. When they were in Balranald around Christmas 1928, the shack where they lived in Boundary Bend burned down and after that they stayed in Balranald. They never came back to live in Boundary Bend.

Reg Dean and the Fishing

In 1917 Jack Dean had moved from Mildura to Boundary Bend to work on a farm for Mrs Alec Conner. In the winter of 1920, he disagreed with the manager about pruning and moved downstream to do house maintenance at Hortico. In February, 1921 the family moved back to Boundary Bend for school. At that time Jack Dean had built a fishing boat of Baltic timber, 18 feet long and 5 feet wide, riveted together. The family had been fishing all along, the boys using string and a stick for line and rod. They had one precious sinker and a thin little hook, a treasure. Still, they caught fish as they were plentiful in the river then.

|

Jack began serious fishing as a professional in 1926. An inspector came and he asked about the nets being used. How many are you using? 25. Is the mesh a legal size? I hope so as Bob O’Bree made them and he does them for other fishermen. The inspector measured them and said that they could be a bit bigger but we’ll pass them this time. Jack was using drum nets and cord nets on a wire frame with wings in front. He’d heard of gill nets but didn’t have any then.

Murray Cod was the only fish worth sending to market as there was no demand for perch or anything else. You were lucky to get paid anything for them. The water then was crystal clear. You could see 6 feet down. Jack had a lump of wood in the boat that he called a knocker. It was to stun a big fish if he pulled it in, so it wouldn’t thrash round and leap out of the boat. A proper knocker was a piece of shovel handle 18 inches or so long. In the 1920s fish were packed in baskets for sending to the Melbourne market. Boxes didn’t come into use till the early 30s'. Blowflies would get in the baskets sometimes and ruin the fish for sale. For a while, washed wheat bags were used to get round the blowfly problem, till they were banned. Beer boxes and sewing machine boxes were also used. They would hold 100 pounds of iced fish when they were used in later years. In the early days there was no such thing as ice. Fishermen would keep the fish in cages in the water in long wire netting things like huge drum nets, until there was a cool spell. Sometimes a big cod would be tethered by putting a string through a bone in its nose and tying it to log. Then they’d kill and clean the fish and hang them on a fence, cover them with wet hessian and fan them to get them as cool as possible. Everyone would take turns to keep fanning them for some hours, and then they were packed in baskets with wet gum leaves. |

The Murray Cod

|

Bob O’Bree would come with his wagonette pulled by two big Clydesdale horses and take the baskets to the rail at Yungera, 4 miles away. He’d take l0 or l2 baskets at a time that was half a ton of fish, each basket would hold 80 or 90 pounds of fish. The train left Yungera at midnight and got in to Melbourne at 3 or 4 o’clock the next afternoon. If the fish didn’t last the journey you might get a blue ticket from the market people, that meant that your fish had gone bad and was Not Fit for Human Consumption. You’d send to two or three agents at a time and compare the prices they gave.

Drum nets were used to catch the fish. They had a cylinder held open by two metal rings and a funnel leading back into the drum and wings out the front to guide the fish in. The wings were held in place with upright pegs. At the back of the drum the mesh was pulled together by a cord which could be loosened to get the fish out. Then it was knotted and the cord went 6 feet to the tailring about the size of a saucer, which was slipped over the tailpeg, set in the bed of the river upstream. The drum net was set so it faced downstream, fish usually swim against the current and l the funnel was designed so that once a fish goes in it can’t tum and swim out again. The whole net was made with a 5 inch mesh. You’d usually make it five and a half to allow for shrinkage when it was tarred and to be on the safe side. It was usually 3 foot 6 across and including wings about 15 feet long. To set it you’d choose a spot on the bank and feel round the bed of the river in front of it with a pole to make sure there were no snags in the way. You had to be a pretty good swimmer and you got to know the stretch of river where you worked pretty well.

Drum nets were used to catch the fish. They had a cylinder held open by two metal rings and a funnel leading back into the drum and wings out the front to guide the fish in. The wings were held in place with upright pegs. At the back of the drum the mesh was pulled together by a cord which could be loosened to get the fish out. Then it was knotted and the cord went 6 feet to the tailring about the size of a saucer, which was slipped over the tailpeg, set in the bed of the river upstream. The drum net was set so it faced downstream, fish usually swim against the current and l the funnel was designed so that once a fish goes in it can’t tum and swim out again. The whole net was made with a 5 inch mesh. You’d usually make it five and a half to allow for shrinkage when it was tarred and to be on the safe side. It was usually 3 foot 6 across and including wings about 15 feet long. To set it you’d choose a spot on the bank and feel round the bed of the river in front of it with a pole to make sure there were no snags in the way. You had to be a pretty good swimmer and you got to know the stretch of river where you worked pretty well.

|

Reg’s son, Johnny, with his 21 lb Murray Cod

|

In 1927 when Reg was about 14, he caught his first big fish. It must have been 50 or 60 pounds. He earned good money for that and left school to join in the fishing game. Jack sewed it in a wet wheat bag and sent it to market by itself. Bob O’Bree gave Reg and Frank Dean 10 nets to work on a one-third basis and as they were juniors his licence covered them. Later they got licences of their own, but the inspectors trusted them to do the right thing. In 1929 when Reg was 16 he went to work fishing for Maldon Bright again on a one-third basis. He would walk a mile and a half from Boundary Bend, row 3 miles upstream setting 50 nets, work in the orchard all day, then row downstream crating the fish (if any) in the wire crate pulled behind the boat. There was not a lot of fish that year, they emptied the Hume weir and treated the last of the water with copper which killed many fish way downstream.

The fishing season was closed from the beginning of September and the agent wrote to Mr Bright asking for all the fish he could send in August, just before the season closed. The price would be up to maybe 4 or 5 pence a pound. There were 3 or 4 boxes in that last consignment and he only got a cheque that was dishonoured for it.

WC Oxley of Beaconsfield supplied the seine twine that was used to make the nets by hand. Out of 100 nets you’d have to replace about 15 every year. Robert O’Bree made some of them, as did Mrs Simmons and the Andersons too. Lindsay Anderson was a very fast maker. He could make a whole net in a day. |

|

Mr Dowie made netting needles from broken axe handles and he’d plane and shape them, notching them at each end. Kids were paid a penny a needle to wind the cord onto them. Each one would hold 30 or 40 yards of cord. It had to be 24 ply for the drum and funnel and only 18 ply for the wings.

Wings were just guides, they didn’t have to be so strong and take the strain like the drums. You’d use a netting board and the needle, the board had to be just right to give the sized mesh that was legal, five inches, with a bit to spare for shrinkage when the net was tarred. |

Tarring the nets was not a good job and every fisherman had to do his own. Nets had to be tarred before use then done again every year. Some even did them every six months and it was definitely a non-smoking job. Tarring was a job for several men working together. They would wear old clothes, gumboots and gloves as tar would get all over the place, especially while spreading the nets out to dry. The tar tank was put up on bricks with a slow fire underneath, beside a big clear claypan. There’d be a big stack of nets ready to do and the men would stand each side of the tank with big hooks to dip 3 or 4 nets at a time in the warm runny tar. They’d leave them in for a couple of seconds and hold them up to drain then take them to the claypan to spread out and dry in the sun. There’d be a stake in the middle of the claypan and the tailrings would go over that with the nets spread in a circle round it. If you left the net in the tar for too long you’d kill the strength of the cord.

When terylene came in the late 40s the tar had to be cooler and you had to be quicker or you’d lose the lot. Cord nets would only last for 2 or 3 years, the cord rots in the water eventually even with the tar. Terylene ones go on for 25 years but they all had to be tarred, tar would seal the knots so they never loosened or came undone.

The fishermen didn’t row their punt by pulling on the oars. They pushed on them and faced the way they were going so they could see what they were doing. Archie Conner was a quick and expert net-setter, he taught others, a couple of strokes on the oars, up with the net, empty it, knot it again and on to the next net. The fish were emptied onto the floor of the boat and everything but cod thrown back into the water. Every couple of nets the cod would be taken to the half submerged punt that Conners had alongside the Etona. It worked like the cages that most of the others had to keep their fish in. They operated 100 nets, with two men working as a team to set and check them. When it came to fish day they’d bring the Etona in to Boundary Bend, pull back the hatch on top of the punt, get in with wading boots on and swoop round with a big landing net to bring out two or three cod at a time, 10, 12, 15 pounders. The deck on the Etona had a railing round it a foot or more high and they’d tip fish out onto it. There’d be these great cod wriggling round all over the place, the town kids watching and marvelling at the sight. Suddenly one of the big fish would give a great leap and a kid would yell "Mr Conner! Mr Conner! A big fish just jumped back into the river!" Mr Conner would look up and say " Did he now boy? Never mind, we’ll catch him again next time". Archie didn’t give a hoot.

When terylene came in the late 40s the tar had to be cooler and you had to be quicker or you’d lose the lot. Cord nets would only last for 2 or 3 years, the cord rots in the water eventually even with the tar. Terylene ones go on for 25 years but they all had to be tarred, tar would seal the knots so they never loosened or came undone.

The fishermen didn’t row their punt by pulling on the oars. They pushed on them and faced the way they were going so they could see what they were doing. Archie Conner was a quick and expert net-setter, he taught others, a couple of strokes on the oars, up with the net, empty it, knot it again and on to the next net. The fish were emptied onto the floor of the boat and everything but cod thrown back into the water. Every couple of nets the cod would be taken to the half submerged punt that Conners had alongside the Etona. It worked like the cages that most of the others had to keep their fish in. They operated 100 nets, with two men working as a team to set and check them. When it came to fish day they’d bring the Etona in to Boundary Bend, pull back the hatch on top of the punt, get in with wading boots on and swoop round with a big landing net to bring out two or three cod at a time, 10, 12, 15 pounders. The deck on the Etona had a railing round it a foot or more high and they’d tip fish out onto it. There’d be these great cod wriggling round all over the place, the town kids watching and marvelling at the sight. Suddenly one of the big fish would give a great leap and a kid would yell "Mr Conner! Mr Conner! A big fish just jumped back into the river!" Mr Conner would look up and say " Did he now boy? Never mind, we’ll catch him again next time". Archie didn’t give a hoot.

|

In 1923 there were plenty of little carp. Bait carp we called them. The sort you have in a fishtank and nothing to do with the European Carp that came 45 years later. They lived and bred in the billabongs and you’d catch them in a dragnet to get bait for the crosslines. They were not a pest like the Euros and didn’t muddy the water or found in the river much. They loved the still water. There are still quite a lot about.

Frank and I would catch frogs for dad to use as bait. Green frogs, tree frogs, marbled frogs, a 100 at a time. Tree frogs have sucker feet and make a rattle sound. Marbled frogs say "Ploonk". The big green frogs go "Ah ah ah ah". There were plenty of frogs in the little lagoon behind Conners and once Frank grabbed, what he thought was a frog swimming towards the lantern light but it was a tiger snake. You could never tell, with just the head showing as they swam, they looked like a frog. |

Bait Carp

|

Yabbie tails were good bait but we had never heard of bardie grubs. You could catch cod using river mussels for bait. At a pinch you could use rabbit guts, centipedes or even bits of smelly long-dead pelican.

It used to be that if there was an inch of rain at Albury or Echuca the rise would come down the river and the fish would be on the bite with the rise. Now with the locks and weirs there are no natural rises in the river. It depends when the water is let down by the lockmasters.

The lagoon behind Conners also had a lot of catfish and you didn’t dare go in the water there with bare feet. You might stand on a catfish spike and that was agony. Now and again we’d get a blackfish. They were 12-18 inches long and shaped like an eel. They had a purple belly and were dark green on the back, with a big mouth like a cod. Sometimes you’d catch a rock or trout cod along with tench and bony bream sometimes called silver perch and Macquarie perch. Butterfish were 6 or 8 inches long, transparent, pale green with a silvery stomach and you could hold one up to the sun and see all its bones. The gudgeon was like a little Murray cod to look at, only about 6 inches long, with little squares of colour along its body, red, brown, green, and black. Redfin was quite rare in the 20s. It reached a peak in the 70s and they’d get up to 5 pounds weight and were very good eating but you didn’t send them to Melbourne. I once caught over 100 of them in Benanee in an hour and a half. Black bream or grunter were good fighters and the biologists called them silver perch although they had a different smell and ate different food. They lived on the bottom in the mud and weeds. There were "Lemia" parasites. They are like a fish flea and were sometimes seen in the 20s. They made a little red pimple with a tail sticking out. It was only on the fish’s skin. They didn’t penetrate the flesh but weakened the fish. You’d see them on a cod in the 20s but later on they almost wiped out the redfin in Benanee.

I only saw 3 platypi in all their years on the river and all were males. There were water rats like big mice with bristly hair and long black and white tails. You could see where they had been but rarely saw one.

In a flood, a bridge of punts that was used up the Murrumbidgee broke up and a badly damaged unit got as far as Boundary Bend. The Deans caught it, repaired it and used it as a houseboat.

It used to be that if there was an inch of rain at Albury or Echuca the rise would come down the river and the fish would be on the bite with the rise. Now with the locks and weirs there are no natural rises in the river. It depends when the water is let down by the lockmasters.

The lagoon behind Conners also had a lot of catfish and you didn’t dare go in the water there with bare feet. You might stand on a catfish spike and that was agony. Now and again we’d get a blackfish. They were 12-18 inches long and shaped like an eel. They had a purple belly and were dark green on the back, with a big mouth like a cod. Sometimes you’d catch a rock or trout cod along with tench and bony bream sometimes called silver perch and Macquarie perch. Butterfish were 6 or 8 inches long, transparent, pale green with a silvery stomach and you could hold one up to the sun and see all its bones. The gudgeon was like a little Murray cod to look at, only about 6 inches long, with little squares of colour along its body, red, brown, green, and black. Redfin was quite rare in the 20s. It reached a peak in the 70s and they’d get up to 5 pounds weight and were very good eating but you didn’t send them to Melbourne. I once caught over 100 of them in Benanee in an hour and a half. Black bream or grunter were good fighters and the biologists called them silver perch although they had a different smell and ate different food. They lived on the bottom in the mud and weeds. There were "Lemia" parasites. They are like a fish flea and were sometimes seen in the 20s. They made a little red pimple with a tail sticking out. It was only on the fish’s skin. They didn’t penetrate the flesh but weakened the fish. You’d see them on a cod in the 20s but later on they almost wiped out the redfin in Benanee.

I only saw 3 platypi in all their years on the river and all were males. There were water rats like big mice with bristly hair and long black and white tails. You could see where they had been but rarely saw one.

In a flood, a bridge of punts that was used up the Murrumbidgee broke up and a badly damaged unit got as far as Boundary Bend. The Deans caught it, repaired it and used it as a houseboat.

Robinvale Soldier’s Settlements and Stories

|

My dad Jack Dean was a competent carpenter. In May 1929 he was allotted a three acre block (number one) on the flats at Robinvale. He became ill without ever taking possession and died a little while later. Frank and I made paddles for the old punt we found abandoned and in November 1930 rowed downriver to live on the 3 acres dad had been allotted. A neighbour Jack Loy told me and Frank to go to Euston and arrange to get a fishing licence at a cost of five shillings each. Licences ran out each November and had to be renewed. Euston police were not water police, but they had to patrol the river and see that things were done properly. They might come along in a canoe, no motors, or they might ride a horse along the bank keeping an eye on things.

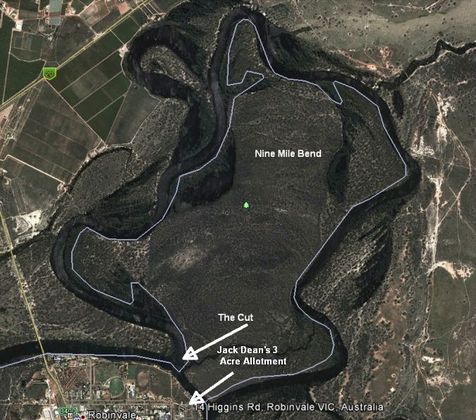

The Murray River at Robinvale had the famous Nine-Mile Bend. This was an island opposite our dad's allotment. This was mine and Frank's Professional Fishing Claim.

Once a year fisheries inspectors would come along in a big yellow motorboat and they would measure the size of the mesh in every net they saw. |

If the mesh was less than 5 inches they would confiscate it, pile it into the boat and when they had a heap they would put them on the bank, cover them with dead leaves and set fire to them. They were illegal. Once near Euston they struck a rough day when they had too many nets on board and the boat sank. They lost most of the nets but the boat was retrieved.

Above is our father's 3 acre allotment that brother Frank took over in 1938. Frank and his wife Silvie were then married in 1940 and lived on the number 1 allotment (Sherringhill) with their children Joycelyn and Robert. I bought the Block 27 further upstream where I later married Evelyn and although Frank and I lived seperately, we continued our fishing partnership. I was married in 1942 and we had 5 children, Norma, John, Deanna, Gail and Rodney and we all lived opposite the end of the later aptly named, Dean Road.

Now settled in to our own lives on our own allotments, we got straight into the fishing again, getting the catch to the railway station any way we could. We would carry the fish in bags, wheeling them on the back of a bike. As time went on we got better organized, got a trailer to cart the fish and had boxes branded with our own name. This continued for many lucrative years. Frank left the fishing later but Evelyn got her licence and our kids helped and we kept going with the fishing for a time.

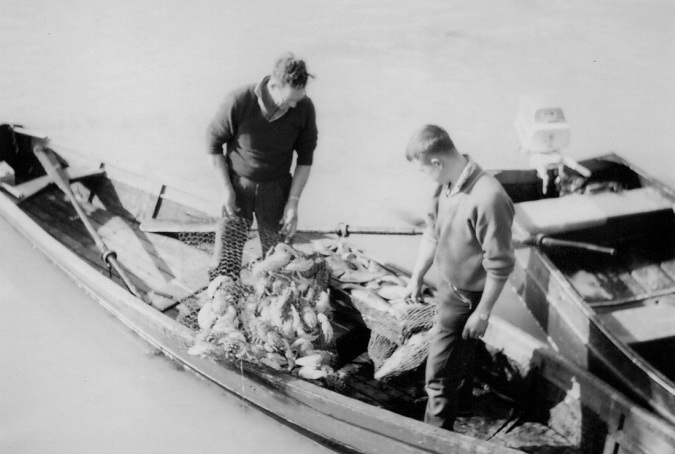

Pictured below is Uncle Gordon and Robert with the day’s catch of Murray Cray, Yellowbelly, Cod and Perch.

Times soon began to get tough in the professional fishing scene on the Murray River. Many arguments against taking fish from the river were becoming more common. There were increasing motor boats and recreational fishermen using the river and professional fishing was being discouraged. The number of nets a professional fisherman was allowed to use was cut to 20. The permissible size for keeping a cod was set at 15 inches. No new licences were being issued. In 1988 Reg relinquished his professional fisherman’s licence, after 62 years straight.

Other Locals I knew at Boundary Bend

A number of professional fishermen and support trades worked out of Boundary Bend

A number of professional fishermen and support trades worked out of Boundary Bend

The O'Bree Family

Robert O’Bree had a wagonette pulled by 2 big Clydesdale horses and he used it to haul fishermen’s packed baskets to the rail, a necessary service. Robert did some fishing besides providing his support services for others. He sometimes had people work his nets on a share basis as he was into so many other things. Their nine sons and one daughter inherited from their parents, qualities of honesty and industry and many were talented in music and singing.

Robert O’Bree had a wagonette pulled by 2 big Clydesdale horses and he used it to haul fishermen’s packed baskets to the rail, a necessary service. Robert did some fishing besides providing his support services for others. He sometimes had people work his nets on a share basis as he was into so many other things. Their nine sons and one daughter inherited from their parents, qualities of honesty and industry and many were talented in music and singing.

|

(further notes thanks to Marita)

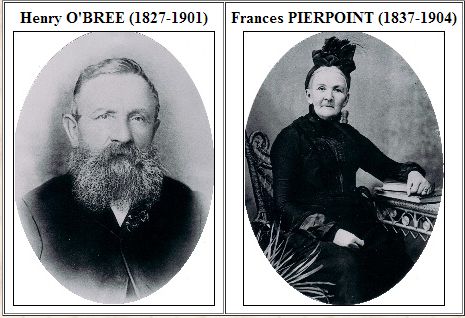

Henry O'Bree, the father of Robert, was born in Hackney on 14th Nov 1827 in the east of London and married Frances Pierpoint from a good standing family in Liverpool. Henry and Frances sailed from Liverpool on an unassisted passage in the "Northern Bride" on March 3rd 1858, and disembarked at Geelong three months later. Robert O’Bree (1879-1948)

|

Footnote: Robert O’Bree, the youngest child of Henry and Frances, features in some of the stories of Reg Dean. Reg's mother Evelyn would also later tell stories to her grandchildren of Robert O'Bree and how wonderful a man he was.

They travelled Victoria by bullock wagon to eventually end up in Stony Crossing, N.S.W. Here Henry tried his hand at grazing but due to adverse conditions had to abandon the idea. Henry and Frances and the younger members of the family moved to Boundary Bend in 1889. Henry bought the "Wine Shades", a saloon, then only a bark hut and rebuilt it with drop logs. It had nine rooms and lined in hessian, which was papered. A very capable man, Henry started the first irrigation scheme at Boundary Bend and the first planting was one acre of mixed fruit trees. Henry died as a result of a bolting coach accident on February 14th 1901, at the age of seventy three and was buried in the Geelong cemetery. His devoted wife Frances died on November 30th 1904, sixty-seven years old. Her remains lie in the Swan Hill cemetery.

The Brights

Maldon Bright employed others to work his 50 nets on a one-third share basis. The agent paid him with a bouncing cheque at the end of the season once. It was for a good lot of fish too. He lived next door to the O’Bree’s and the wagonette was handy for him when he needed it.

Maldon Bright employed others to work his 50 nets on a one-third share basis. The agent paid him with a bouncing cheque at the end of the season once. It was for a good lot of fish too. He lived next door to the O’Bree’s and the wagonette was handy for him when he needed it.

The Connor Family

Archie Conner was the best fisherman. He used to go up the Murrumbidgee fishing as far as Balranald sometimes. He had the woodfired paddle steamer “Blighty” at first, then the “Etona”, which had been a complete little travelling church when he bought it.

Archie Conner was the best fisherman. He used to go up the Murrumbidgee fishing as far as Balranald sometimes. He had the woodfired paddle steamer “Blighty” at first, then the “Etona”, which had been a complete little travelling church when he bought it.

|

Arch Conner, 1886-1980, spent a large part of his life fishing on the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers. Arch owned 'Etona' and made many mercy missions along the flooded Murrumbidgee in the Balranald. Despite living the hard life, Arch always tried to be a good family man and reserve his Sundays for family and Church. Arch Conner, was one of all those who worked and strived to build river communities like Boundary Bend. From 1891 to 1913 the Church of England provided a floating mission for the isolated settlers and communities along the River Murray. The paddle steamer had a chapel. Built at Milang, the Etona, was named after Eton College, which had provided financial support. It travelled between Goolwa and the Victorian border, provided pastoral care at stations, farms and woodcutters camps, as well as to fisherman, river boat families and small settlements.

Pictured left, Archibald Connor, and below: In around 1913, he became the owner and skipper of the paddle ship 'Etona’ ca.1898. |

The Bennetts

Sam Bennett had a paddle boat called the “Britannia”. His son Vic helped him at times and they would go up towards Balranald fishing. Bennett didn’t know the river like Archie Conner did and he wasn’t popular with the other fishermen.

The Shimmins

George Shimmins had a 2 acre block on the rise behind where Nan Conner was. He built a 4 roomed weatherboard house there. Fishing was his main game. Sometimes people would rent his house.

The Burleys

Bill Burley was a German. He fished a stretch of river below Boundary Bend and when he died there was a struggle to take over his notably good patch. Archie Conner got there first but Bennett’s continual shocking threatening language drove him away and Bennett took over.

The Dowies

Mr Dowie made netting needles from broken axe handles. He would cut, plane and smooth them, then notch them at each end. Kids would be paid to wind the cord onto the needles. Each would hold 30 or 40 yards of cord. The netmakers could work much faster if their needles were already wound for them. It was a tedious job. Robert O’Bree also made nets for other people, as did the Andersons and Mrs Simmons. The Pearce family fished too, but it was just for themselves. They didn’t send any to market.

Boundary Bend Supplies

A Queensland firm made bully beef sold in a pyramid shaped tin. That was a treat. At one stage groceries could be ordered from Piangil, upstream, a fair way and delivered with the mail by Bill Lee who drove a Dodge truck.

Boundary Bend was so small it didn’t have a proper shop. In 1924, two pommie men, Gartland and Ormisher, probably relatives, took over a bag shack between the river and the Wine Shades, built a little lean-to on the side and began to sell things like tea, sugar, flour, lollies and biscuits. They couldn’t make a go of that. Gartland left and Ormisher went to Yungera where he continued selling groceries. People had to walk the 4 miles to the rail head for any sort of a shop. That place did no good either. Ormisher left and Boundary Bend people had to go the 11 miles to Koolooonong, a bigger centre then. If you had to walk, you couldn’t do the 22 miles in one day and you’d sleep in a farmer’s shed on the way back.

There was an Indian hawker who came now and then. He was called Sultan Mohammed. He sold sewing materials, cups, plates, working clothes like hats, socks, shirts and trousers, things that didn’t perish. He had two lovely big Clydesdale horses to pull his covered van and he used to stop in the Bend awhile to rest his horses. He treated his horses as if they were his children. He had a white sheet that he put down beside his van when he was praying, he was a Muslim.

Sam Bennett had a paddle boat called the “Britannia”. His son Vic helped him at times and they would go up towards Balranald fishing. Bennett didn’t know the river like Archie Conner did and he wasn’t popular with the other fishermen.

The Shimmins

George Shimmins had a 2 acre block on the rise behind where Nan Conner was. He built a 4 roomed weatherboard house there. Fishing was his main game. Sometimes people would rent his house.

The Burleys

Bill Burley was a German. He fished a stretch of river below Boundary Bend and when he died there was a struggle to take over his notably good patch. Archie Conner got there first but Bennett’s continual shocking threatening language drove him away and Bennett took over.

The Dowies

Mr Dowie made netting needles from broken axe handles. He would cut, plane and smooth them, then notch them at each end. Kids would be paid to wind the cord onto the needles. Each would hold 30 or 40 yards of cord. The netmakers could work much faster if their needles were already wound for them. It was a tedious job. Robert O’Bree also made nets for other people, as did the Andersons and Mrs Simmons. The Pearce family fished too, but it was just for themselves. They didn’t send any to market.

Boundary Bend Supplies

A Queensland firm made bully beef sold in a pyramid shaped tin. That was a treat. At one stage groceries could be ordered from Piangil, upstream, a fair way and delivered with the mail by Bill Lee who drove a Dodge truck.

Boundary Bend was so small it didn’t have a proper shop. In 1924, two pommie men, Gartland and Ormisher, probably relatives, took over a bag shack between the river and the Wine Shades, built a little lean-to on the side and began to sell things like tea, sugar, flour, lollies and biscuits. They couldn’t make a go of that. Gartland left and Ormisher went to Yungera where he continued selling groceries. People had to walk the 4 miles to the rail head for any sort of a shop. That place did no good either. Ormisher left and Boundary Bend people had to go the 11 miles to Koolooonong, a bigger centre then. If you had to walk, you couldn’t do the 22 miles in one day and you’d sleep in a farmer’s shed on the way back.

There was an Indian hawker who came now and then. He was called Sultan Mohammed. He sold sewing materials, cups, plates, working clothes like hats, socks, shirts and trousers, things that didn’t perish. He had two lovely big Clydesdale horses to pull his covered van and he used to stop in the Bend awhile to rest his horses. He treated his horses as if they were his children. He had a white sheet that he put down beside his van when he was praying, he was a Muslim.

The Yungera Railway Line

There was a rail head at Yungera that was a direct line to Melbourne and the fish would be sent from there. Yungera was 4 miles out of Boundary Bend towards Kooloonong. The train would leave at midnight and get to Melbourne at 2 or 3 o’clock the next afternoon, which was a pretty quick trip in those days. The rail head was known as "Yunjeera" and the place on the river, spelled the same, was pronounced Youngra, so the difference was plain. It must have been an Aboriginal name for the area in the old days.

The Yungera Line still provides the longest passenger rail service in Victoria, which currently operates entirely within the State of Victoria between Melbourne and Swan Hill. The service is operated by V/Line Passenger with intermediate stops north of Bendigo at Eaglehawk, Dingee, Pyramid and Kerang.

To the north of Swan Hill, the line continues to Piangil to serve a number of grain silos. Beyond Piangil the line has been removed although a number of grain silos still exist that are now served by road.

There was a rail head at Yungera that was a direct line to Melbourne and the fish would be sent from there. Yungera was 4 miles out of Boundary Bend towards Kooloonong. The train would leave at midnight and get to Melbourne at 2 or 3 o’clock the next afternoon, which was a pretty quick trip in those days. The rail head was known as "Yunjeera" and the place on the river, spelled the same, was pronounced Youngra, so the difference was plain. It must have been an Aboriginal name for the area in the old days.

The Yungera Line still provides the longest passenger rail service in Victoria, which currently operates entirely within the State of Victoria between Melbourne and Swan Hill. The service is operated by V/Line Passenger with intermediate stops north of Bendigo at Eaglehawk, Dingee, Pyramid and Kerang.

To the north of Swan Hill, the line continues to Piangil to serve a number of grain silos. Beyond Piangil the line has been removed although a number of grain silos still exist that are now served by road.

Added Story

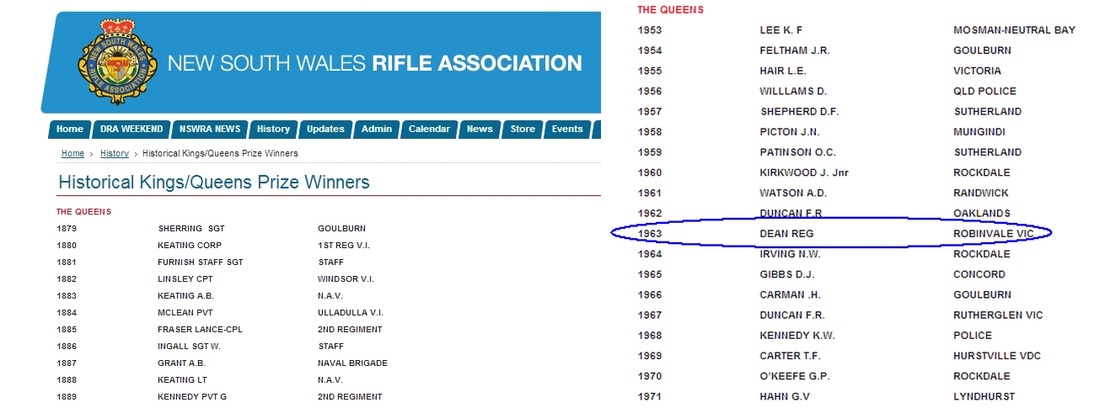

Queens Shoot

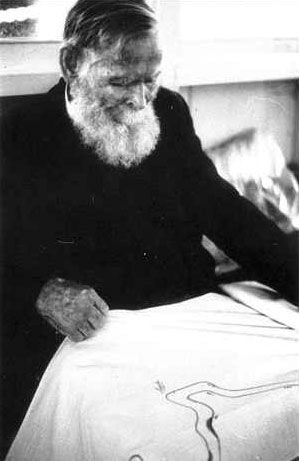

Reg Dean was talented in many ways. One was shooting. He won the prestigious Queens Shoot, held in Tasmania in 1963. This NSW Rifle Association completion attracts .303 rifle shooters (WW2 rifle used by the diggers) from all over Australia every year. Then as a sideline business, he ordered in .303 barrels, stocks and parts and assembled, sighted them in and sold them to fellow shooters. They sold well as they were built with great care and were personally precision sighted. I can remember seeing him in his neat and organized workshop gleaning his eye over the barrels and polishing them up ready for sale.

It is interesting to note that the inaugural winner of the Queen’s Shoot in 1879, was Sgt Sherring. Reg’s mother was formally Evelyn Emily Sherring. The possibility of being related through the English heritage is a possibility.

Reg Dean was talented in many ways. One was shooting. He won the prestigious Queens Shoot, held in Tasmania in 1963. This NSW Rifle Association completion attracts .303 rifle shooters (WW2 rifle used by the diggers) from all over Australia every year. Then as a sideline business, he ordered in .303 barrels, stocks and parts and assembled, sighted them in and sold them to fellow shooters. They sold well as they were built with great care and were personally precision sighted. I can remember seeing him in his neat and organized workshop gleaning his eye over the barrels and polishing them up ready for sale.

It is interesting to note that the inaugural winner of the Queen’s Shoot in 1879, was Sgt Sherring. Reg’s mother was formally Evelyn Emily Sherring. The possibility of being related through the English heritage is a possibility.